【SMM Analysis】Global Aluminium Scrap Markets Series (3) Recycling the Region: ASEAN’s Aluminium Scrap Trade Amid a Shifting Global Economy

Bridging Oceans: ASEAN’s Pivotal Role in the Global Aluminium Scrap Trade

Southeast Asia (SEA), represented by the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN), serves as a critical trade bridge linking Western and Eastern markets across the Indian and Pacific Oceans. Among the many commodities flowing through the region, aluminium stands out as one of the most significant, with several ASEAN countries playing key roles in trading, recycling, and processing.

Thailand, Malaysia, and Vietnam have long been integral players in the aluminium scrap market, each leveraging unique advantages in logistics, industrial capability, or regulatory environments. In recent years, the global shortage of primary aluminium and the growing emphasis on low-carbon manufacturing have elevated aluminium scrap as a viable, environmentally friendly, and cost-effective alternative. Producing recycled aluminium saves over 95% of the energy and carbon emissions compared to primary aluminium, making it essential for meeting both sustainability targets and economic goals.

Although ASEAN countries share an interest in these benefits, their approaches differ significantly. Some states have welcomed the scrap aluminium trade as an industrial opportunity, while others have tightened restrictions to prevent becoming “dumping grounds” for foreign waste. With global demand for low-carbon materials rising and primary aluminium production remaining highly carbon-intensive, ASEAN’s policy diversity will profoundly shape its collective path forward.

Cross-Currents of Trade: Mapping ASEAN’s Aluminium Scrap Flows

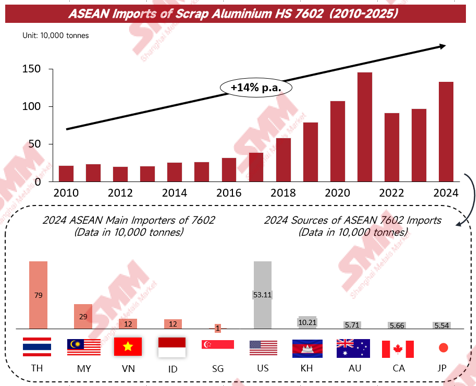

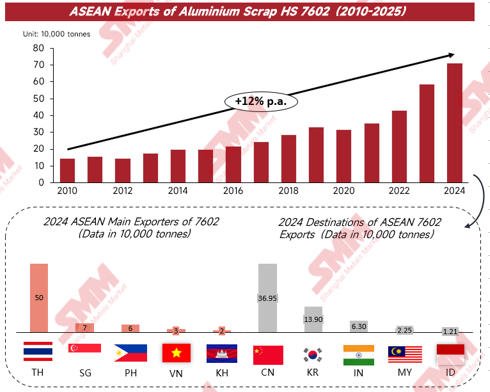

In 2024, ASEAN imported 13.3 million tonnes and exported 7.1 million tonnes of aluminium scrap (HS 7602.00).

- Thailand dominated regional imports with 7.9 million tonnes (59%), followed by Malaysia (2.9 million tonnes, 22%), and both Vietnam and Indonesia (1.2 million tonnes each, 9%). Together, these four accounted for 99% of ASEAN’s total aluminium scrap imports.

- The United States was the largest exporter to ASEAN, shipping 53.11 million tonnes (40% of ASEAN’s imports). Cambodia ranked second, with 99% of its scrap exports sent to Thailand, while Australia, Canada, and Japan each exported 5.5–6 million tonnes to the region.

In export terms, Thailand again led with 5 million tonnes (70.5% of ASEAN’s total). Singapore and the Philippines followed with 7 million and 6 million tonnes, respectively, together representing 18.5% of total exports. Cambodia and Vietnam each exported less than 3 million tonnes in 2024. Malaysia’s export data, however, varies significantly depending on the database used, discrepancies of several million tonnes exist between reported exports and partner import records.

ASEAN primarily trades aluminium scrap grades such as Tense, Talon, and Taint/Tabor, while UBCs (Used Beverage Cans) form another significant flow, especially in Cambodia, Vietnam, and Thailand. The region’s secondary aluminium production largely centres on ADC12 ingots, the most widely produced and exported downstream product.

Hubs, Controls, and Contradictions: The Uneven Rise of ASEAN’s Scrap Giants

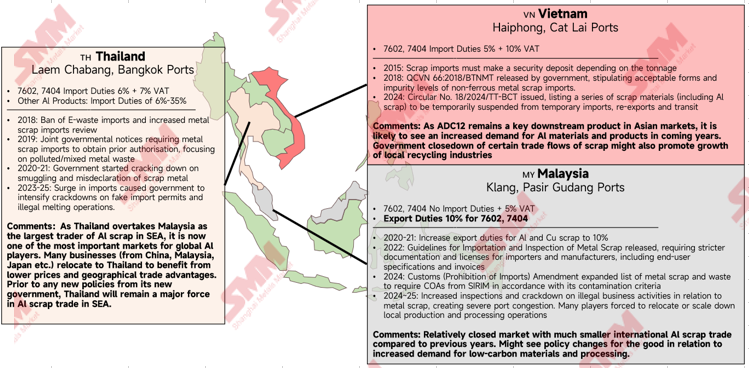

Strategically located between the Malacca Strait and the South China Sea, Thailand has evolved into ASEAN’s largest aluminium scrap trading and processing hub, surpassing Malaysia’s earlier dominance. Since the early 2020s, the Thai government has tightened controls in alignment with the Basel Convention, banning e-waste imports and cracking down on illegal scrap trading networks.

With a new prime minister taking office in September 2025, there have been no indications of further policy changes affecting scrap metal trade. If the regulatory environment remains stable, Thailand is likely to maintain its dominance thanks to its geographic advantages and vast processing capacity, particularly for ADC12 production. As the global market pivots toward low-carbon materials, aluminium scrap will continue to be a strategic asset underpinning Thailand’s sustainability and manufacturing goals.

Vietnam has become a major producer and recycler of aluminium scrap, transforming both domestic and imported materials into products such as ADC12 and UBC remelted ingots. Policy tightening began in 2015 with import security deposits based on tonnage, followed by 2018 regulations specifying allowable impurity levels for non-ferrous scrap. In 2024, the government announced that temporary imports, re-exports, and transits of aluminium scrap (HS 7602) would be suspended from 2025 to 2030.

Despite this, Vietnam remains a critical supplier of recycled aluminium products to China and regional markets, and demand for its scrap-based materials is expected to grow. Local recyclers may capitalize on the re-export suspension by expanding domestic processing capacity to fill external supply gaps, particularly in high-demand categories like UBCs.

Malaysia, once a dominant aluminium scrap hub, saw its position weaken following an export duty increase to 10% on HS 7602 and the imposition of stringent import purity standards (minimum 99.75% metal content, maximum 0.25% impurities). Under SIRIM’s regulations, imported scrap must not include hazardous materials or particles below 5 mm. These measures — while aimed at compliance and environmental protection, led to port congestion, inspection delays, and illegal trading activity, particularly at Port Klang. The situation was further complicated by the Red Sea crisis, which disrupted shipping schedules and diverted cargo to Thailand.

Malaysia’s future role depends on whether it can balance compliance with competitiveness. If the government eases trade friction and reinvests in the sector, Malaysia could reclaim a pivotal position as an ASEAN aluminium intermediary, supported by strong infrastructure, favourable geography, and close economic ties with China and India.

Growth Within Limits: Recycling Potential and Structural Barriers in ASEAN

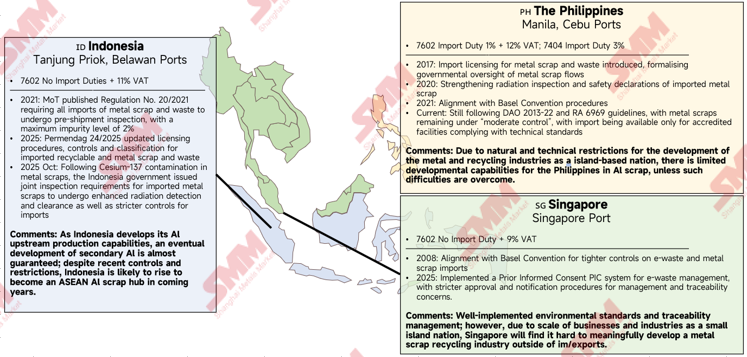

Beyond the top three producers, Indonesia, Singapore, and the Philippines represent ASEAN’s next tier in secondary aluminium trade and recycling.

Indonesia began requiring pre-shipment inspections for all metal scrap imports in 2021, capping impurity levels at 2%. In 2025, the government tightened classification and licensing rules for recyclable metal waste. A major incident in October 2025, where Cesium-137 contamination was discovered in 22 facilities at the Modern Cikande Industrial Estate, prompted even stricter radiation screening for imported scrap.

Although regulations are tightening, Indonesia’s rapidly expanding upstream aluminium industry (notably in smelting and refining) positions it to become a major secondary aluminium producer in the medium term, leveraging its industrial scale and resource base.

The Philippines began formalizing oversight of scrap metal trade in 2017, introducing radiation safety inspections by 2020 and 2021, alongside Basel Convention alignment.

Similarly, Singapore, which acceded to the Basel Convention in 2008, has maintained tight controls on e-waste and metal scrap. In 2025, it introduced a Prior Informed Consent (PIC) system for e-waste traceability, indirectly affecting scrap metal management.

However, both states face inherent constraints. Singapore’s limited land area restricts it to a trading-hub role, while the Philippines lacks sufficient infrastructure for large-scale recycling. Substantial investment and modernization would be required before either country could develop significant secondary aluminium production capacity.

Peripheral Players and Missed Potential: The Margins of ASEAN’s Aluminium Loop

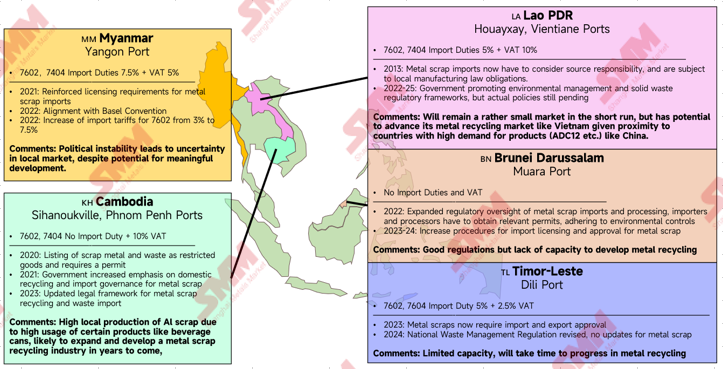

The remaining ASEAN members, Myanmar, Lao PDR, Cambodia, Brunei Darussalam, and Timor-Leste, currently have minimal infrastructure or policy frameworks to support secondary aluminium development.

Among these, Cambodia shows the most potential due to its high domestic generation of aluminium scrap, particularly from UBCs. It already serves as a key supplier of scrap aluminium to Thailand. With proper investment in recycling infrastructure, Cambodia could emerge as a medium-scale processing hub within ASEAN.

Lao PDR, sharing borders and close ties with China, also presents long-term potential. However, its landlocked geography and dependence on the Mekong River for trade pose logistical barriers to large-scale scrap imports. If addressed, Laos could emulate Vietnam’s model, a strong secondary aluminium exporter to China.

Myanmar, despite being a modest importer and exporter, remains hindered by political instability, which discourages foreign investment and disrupts trade. Brunei Darussalam and Timor-Leste, meanwhile, are smaller economies focused on other development priorities, and secondary aluminium will likely remain a low policy priority for the foreseeable future.

Illegal Pathways and the Shadow Economy: Smuggling in ASEAN’s Scrap Trade

Illegal smuggling of aluminium scrap has emerged as a persistent challenge across Southeast Asia, reflecting both the fragmented nature of regional trade policies and the widening divide between demand and availability. In countries such as Thailand and Malaysia, recurring crackdowns have exposed complex cross-border smuggling networks that exploit porous borders, inconsistent customs oversight, and uneven tariff regimes among ASEAN members. Much of this illicit activity involves misdeclaration of scrap categories, transshipment through third-party countries, and undocumented coastal shipments that evade formal reporting systems. In May of 2025, Malaysia seized 272.6 tonnes of scrap metal in the West Port Free Zone, and in July just seized 1960 tonnes of scrap metal in Port Klang brought in without an import permit and wrongfully declared as aluminium alloys, minerals and unprocessed aluminium.

These informal flows not only distort market pricing and weaken legitimate recyclers but also complicate environmental oversight by obscuring the origin, grade, and contamination levels of recycled materials. The absence of a unified ASEAN framework for scrap traceability or customs data exchange allows smugglers to operate across regulatory blind spots, shifting material through jurisdictions with weaker import standards or enforcement capacity. In June 2025, Thailand took legal action against a large company that was involved in the import of aluminium and copper scrap for processing, and leaving pollutants and untreated wastewater in Thailand, alongside unauthorised and imporper company operations. Unless stronger intergovernmental coordination, shared digital tracking systems, and harmonised import regulations are established, illegal smuggling will continue to function as a shadow industry, eroding both policy integrity and ASEAN’s credibility in advancing sustainable metal trade.

Outlook: Strategic Trade Shifts, Green Demand, and Price Pressures

Looking ahead, ASEAN stands at the confluence of several transformative trade and market forces that could redefine its aluminium scrap landscape. The recent US-ASEAN agreements on critical minerals, signed under President Trump’s administration in late 2025, are expected to accelerate American and allied investment into the region’s refining and recycling capacity, particularly as secondary aluminium gains recognition as a low-carbon, secure supply source. Parallel developments, such as ASEAN’s ongoing free-trade negotiations with Canada and the upgrade of the ASEAN–China Free Trade Area (ACFTA 3.0), further highlight an emerging regional emphasis on green-economy alignment, digital traceability, and circular-supply-chain development.

At the same time, global demand for low-carbon aluminium is rising sharply, as automotive, construction, and electronics manufacturers commit to emission reductions. This shift could position ASEAN as a competitive supplier of low-carbon recycled aluminium, provided that its scrap flows are formalised, traceable, and environmentally compliant. However, the recent surge in LME aluminium prices in October has introduced volatility that threatens to squeeze scrap recyclers that trade scrap based upon LME discounts; as SEA’s scrap prices climb, sellers are increasingly holding inventories in anticipation of further gains, while buyers hesitate amid uncertain margins. If this imbalance persists, liquidity in the scrap market could tighten, disrupting trade flows and undermining ASEAN’s broader ambition to establish a resilient, circular aluminium economy.

Taken together, ASEAN’s challenge is twofold: to leverage new trade frameworks and the low-carbon transition to climb the value chain, while stabilising its domestic scrap ecosystem against price shocks and regulatory fragmentation. A coordinated policy approach — linking trade, environmental standards, and digital customs transparency — will determine whether the region emerges as a global hub for sustainable aluminium or remains vulnerable to cyclical and policy-driven disruptions.

Conclusion: Towards a Coherent and Circular ASEAN Aluminium Future

Ultimately, ASEAN’s aluminium narrative mirrors the broader challenge facing emerging economies: how to pursue industrial growth while embedding environmental accountability and market stability. The convergence of new trade partnerships with the United States, Canada, and China, rising demand for low-carbon products, and volatile commodity prices has placed the region at a pivotal crossroads. The coming years will test whether ASEAN can evolve from a fragmented collection of national scrap markets into an integrated, transparent, and climate-aligned metals ecosystem.

Success will hinge on more than trade diplomacy alone. It will require policy coherence, digital traceability, and regional investment in cleaner technologies, from efficient furnaces and renewable-powered smelters to AI-based scrap sorting and carbon-footprint verification systems. Governments must also close the gap between environmental policy ambition and implementation, ensuring that small- and medium-sized recyclers are not excluded from the low-carbon transition.

In this sense, aluminium scrap is no longer a peripheral commodity but a strategic industrial feedstock central to ASEAN’s circular-economy future. By treating recycling as part of the region’s critical-minerals security architecture, ASEAN can strengthen both its trade position and sustainability credentials. If the region succeeds in harmonising standards and deepening cooperation, it could transform its role in the global metals chain — from supplier of inexpensive scrap to trusted producer of certified, low-carbon recycled aluminium that anchors the next generation of green industries.