1.Introduction: The Predicament of Low-Grade Copper Scrap — “Nowhere to Go”

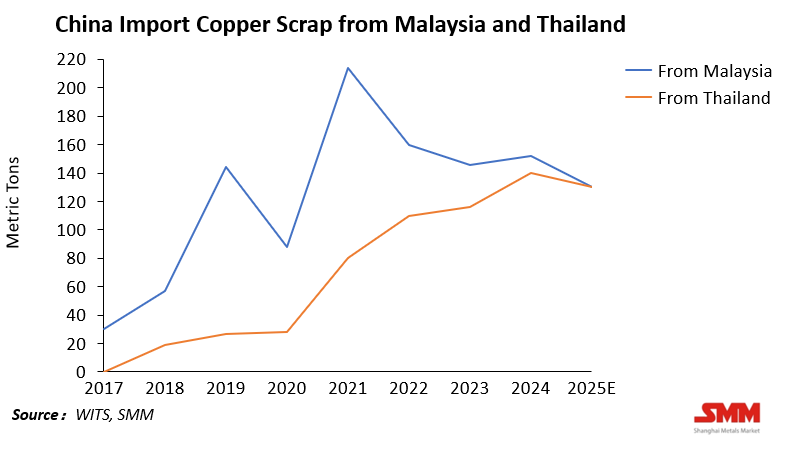

Over the past decade, global copper scrap flows have undergone two structural shifts. The first began with China’s restrictions on “foreign waste” imports, which diverted large volumes of European and American copper scrap to Southeast Asian countries for sorting and preliminary processing before being re-exported to China. Malaysia, Vietnam, and Thailand once served as crucial transit hubs in this supply chain.

In recent years, however, as Southeast Asian nations have tightened import standards and strengthened environmental oversight, this trade model — characterized by light processing and re-export — has entered a “semi-shutdown” stage. Meanwhile, Western countries, motivated by the strategic importance of copper resources and circular economy goals, have increasingly retained high-quality copper scrap for domestic use. This has further reduced the volume of recyclable copper materials circulating in international markets.

As a result, large quantities of low- and medium-grade copper scrap are now effectively trapped: unable to enter China, the world’s largest copper consumer, and increasingly blocked by Southeast Asian import restrictions — leaving them with “nowhere to go.”

Against this backdrop, traders and processing companies are actively seeking new transit and preliminary treatment hubs to absorb displaced low-grade material. Among potential regions — such as India, the Middle East, and South America — the Middle East is emerging as a promising candidate, thanks to its open trade regime, cost advantages, and strategic logistics positioning.

2.The End of an Era: Southeast Asia’s Decline as a Low-Grade Copper Scrap Transit Hub

Since China’s solid waste import ban, Southeast Asia became a major global copper scrap transit region. Countries such as Malaysia and Thailand absorbed significant volumes of low-grade copper scrap from Europe and the United States, carrying out basic processes like sorting, cutting, and repackaging before re-exporting to China. However, this era of Southeast Asia as the world’s copper scrap “gateway” is nearing its end.

In 2021, Malaysia implemented new SIRIM standards, sharply raising the import threshold — requiring copper content of at least 94.75%. Large quantities of low-grade copper scrap were rejected or stranded at ports. As a result, many long-established recycling and processing companies relocated, with a substantial share moving to Thailand, where policies were then more relaxed.

Yet since 2023, Thailand has also tightened its waste metal import and licensing systems, while cracking down on smuggling and false declarations. In essence, Thailand is becoming “the next Malaysia.” With comprehensive enforcement, extended customs clearance times, and higher compliance costs, Southeast Asia’s role as the center of low-grade copper scrap re-export is rapidly fading. Traders are now forced to search for new destinations — and the Middle East has entered their radar as the next potential processing hub.

3.The Middle East’s Potential: Policy Flexibility + Cost Advantage + Strategic Location

As global traders seek new processing bases, the Middle East’s unique combination of advantages has positioned it as an emerging hotspot for copper scrap re-export and light processing. Its appeal stems from three key dimensions: lenient policies, competitive cost structures, and strategic geographic and trade positioning.

(1) Policy Flexibility

The Middle East’s relatively relaxed regulatory environment is currently its greatest draw. In sharp contrast to Southeast Asia’s rising environmental barriers, most Middle Eastern countries — particularly the UAE, Oman, and Saudi Arabia — have yet to introduce stringent restrictions on copper scrap imports.

Regional governments prioritize attracting foreign investment and industrial diversification over environmental constraints. Free zones such as Jebel Ali Free Zone (JAFZA) and Khalifa Economic Zones Abu Dhabi (KEZAD) in the UAE, and Sohar Free Zone in Oman, offer incentives including zero tariffs and license-free imports. For traders seeking efficient customs clearance and minimal bureaucracy, this regulatory openness offers an unparalleled advantage.

(2) Cost Competitiveness

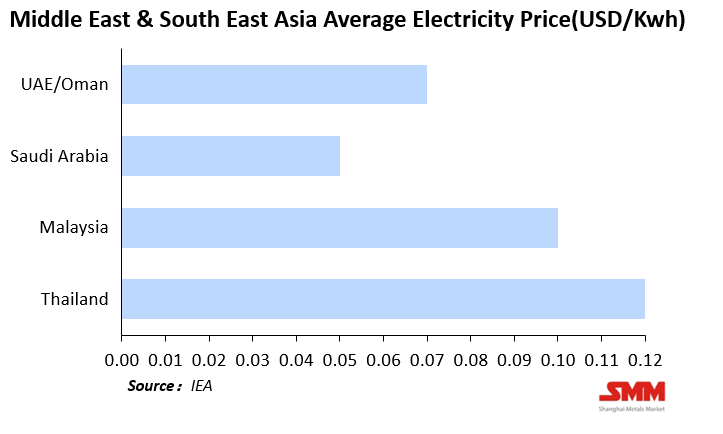

The Middle East also enjoys a significant cost edge, particularly in energy. According to data from the International Energy Agency (IEA) and regional regulators:

This substantial energy cost gap translates into strong price competitiveness. Combined with modern logistics infrastructure and low warehousing costs, Middle Eastern ports can move materials efficiently. Although local labor costs are higher, industrial zones rely heavily on migrant workers from India, Pakistan, and Bangladesh, keeping labor expenses for light processing roughly on par with Southeast Asia.

(3) Strategic Location and Infrastructure

Geographically, the Middle East lies at the crossroads of Asia, Europe, and Africa — connecting westward to European markets and eastward to China, India, and Southeast Asia. Its world-class deepwater ports — Jebel Ali, Sohar, and Dammam, among others — provide natural advantages for re-export and transit trade.

These ports enable a complete cycle of import–processing–re-export, supporting operations from warehousing and sorting to repackaging and even preliminary smelting — reinforcing the region’s potential as a future copper scrap processing hub.

4.Emerging Evidence: A Nascent “Collection and Distribution” Function

Though the Middle East’s copper scrap processing sector remains nascent, several developments already suggest its gradual emergence as a new node for global copper scrap transit and light processing.

(1) The UAE: Becoming the Region’s Trade Nucleus

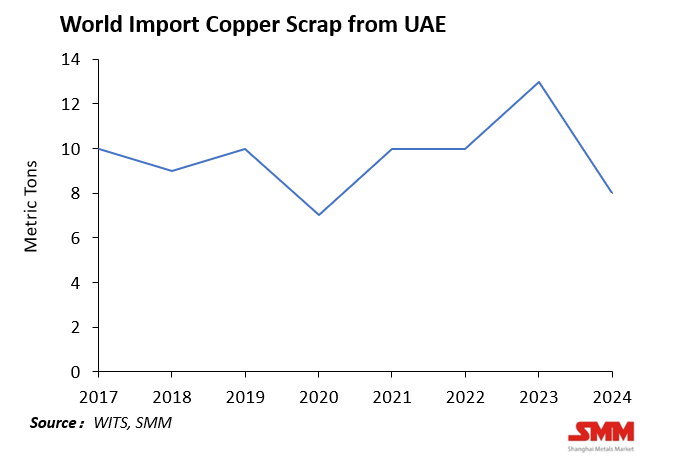

In Dubai and Sharjah, a growing cluster of companies now specialize in sorting, packing, and re-exporting copper scrap. Many are backed by investors from India, Pakistan, and China, leveraging Jebel Ali Port’s efficient clearance and free zone benefits to process material sourced from Europe, the U.S., and Africa before re-exporting to Asia.

Some firms have already installed preliminary processing lines to upgrade copper purity to meet Chinese or Indian import standards. Though still modest in scale, this trend signals that the UAE is taking on an intermediary role in the global copper scrap trade.

Notably, since 2024, the UAE has imposed a 400-dirham (≈ RMB 775) per ton export tariff on copper scrap. While exports dipped briefly, the policy may, in the long run, encourage more value-added processing, gradually shifting the UAE from a simple sorting hub to a light-manufacturing center.

(2) Oman: Building a Policy-Based Industrial Cluster

Oman has actively promoted metal recycling within its “Metals Cluster” at Sohar Port, established in recent years. The cluster hosts copper, aluminum, and steel recycling projects and has attracted investors from India, Turkey, and Europe. Some firms have started conducting light sorting and repackaging locally.

Moreover, Oman’s “Industrial Development Strategy 2040” explicitly identifies metal recycling and re-export capacity as pillars of industrial diversification — providing a solid policy foundation for legal copper scrap import and processing.

(3) Saudi Arabia: Toward a Domestic Circular Economy

Although Saudi copper scrap imports remain limited, its National Circular Economy Strategy emphasizes developing metal recycling systems and establishing industrial parks for secondary metal production, with foreign investment participation. As infrastructure and interregional coordination improve, Saudi Arabia could become a key redistribution hub within the Middle East’s internal copper scrap network.

Overall, while the Middle East lacks large-scale smelting or refining capacity, its transit, warehousing, and preliminary processing capabilities are developing rapidly. From active free zones and port logistics efficiency to national industrial policies, these signals all point in one direction: the Middle East is being selected by the global copper scrap trade as the next potential processing and distribution hub, following Southeast Asia’s model.

5.Risks and Uncertainties

Despite its potential, the Middle East’s path toward becoming a global copper scrap hub faces multiple uncertainties — from regulatory gaps to geopolitical challenges.

(1) Incomplete Policy and Regulatory Frameworks

Much like early-stage Southeast Asia, most Middle Eastern nations still lack systematic environmental oversight and standardized import criteria for copper scrap. Aside from the UAE and Oman, few have clear rules regarding copper quality, contamination levels, or traceability.

While this policy vacuum offers short-term trade advantages, it carries long-term risks of policy reversals. Should international partners or major importers demand higher environmental standards, the region could face the same tightening cycle that Southeast Asia experienced.

(2) Environmental and Reputational Risks

Middle Eastern governments are promoting “green industry” and circular economy narratives. However, poor environmental management or illicit trade at early stages could easily tarnish these efforts. For image-conscious economies like the UAE and Saudi Arabia, which seek to brand themselves as sustainable investment destinations, being labeled a “low-end waste processing hub” would be reputationally damaging.

Hence, to sustain growth, the region must establish traceable, compliant, and low-emission processing frameworks — even at the cost of rising operational expenses.

(3) Geopolitical and Logistics Risks

The Middle East remains geopolitically sensitive. Issues such as Red Sea maritime security, Iran–Gulf tensions, and regional conflicts could directly disrupt copper scrap transport routes.

Moreover, the region’s internal logistics networks remain fragmented — while its ports are world-class, interconnectivity is limited, and cross-border transit often relies on a handful of designated corridors. These factors pose systemic risks under global supply chain disruptions.

6.Conclusion: The Middle East at a “Policy Window Moment”

The evolution of global copper scrap flows has always reflected shifts in policy and cost structures. China’s import ban once fueled Southeast Asia’s rise; now, Southeast Asia’s tightening is opening a new window for the Middle East.

With open trade systems, low energy costs, and a strategic geographic position, the Middle East has the fundamental prerequisites to become the new global hub for low-grade copper scrap.

However, potential does not automatically translate into reality. To truly capture this industrial migration opportunity, Middle Eastern economies must balance speed with structure — maintaining openness and trade efficiency while establishing basic environmental, traceability, and compliance frameworks to avoid repeating Southeast Asia’s “boom-then-restriction” cycle.

Ultimately, global copper scrap flows represent a continuous interplay of policy, cost, and geopolitics. Today, the Middle East stands where Southeast Asia was a decade ago: abundant opportunities, but a narrow window. If the region can institutionalize its early advantages and build an integrated industrial ecosystem, it could well become a pivotal node in the next phase of the global recycled copper landscape.